Chapter 12: Serendipitous Sightseeing

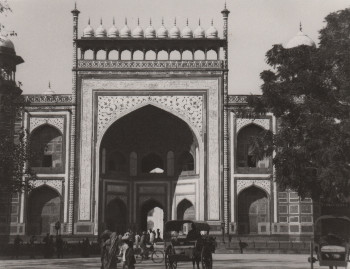

When my sightseeing plans were complete, I organised a party of twelve B.O.R.s who were sufficiently interested to come to Agra with me for a weekend to see the sights. We set off by train from Delhi after work on Friday, the 21st of February. After a journey of about 120 miles, we reached Agra and made our way to a kind of Forces Hostel (rather like a Y.M.C.A.), which had been recommended to me. We had good rooms here and spent the rest of the evening in a large common room which we had to ourselves. Here, I narrowly beat one of the men in a game of chess. My win was by luck rather than any skill on my part as I was never a good chess player. Next morning, I secured a native guide who knew Agra and the surrounding area, and we set off for the Taj Mahal. The hostel was to the south of Agra city and we soon reached the Taj on the south bank of the Jumna river. The Taj complex is entered through an imposing gateway fronting on to a wide open space.

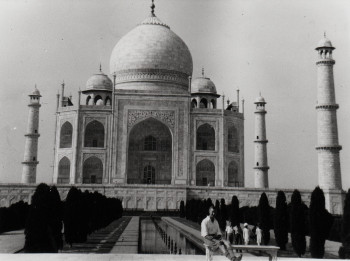

It is said that when the monument was completed, this area was full of bamboo and timber scaffolding, and the emperor being impatient to see the finished monument asked his minister how long it would take to remove it all. He was told that it would take at least a year, but not having the patience to wait so long, the emperor declared that the populace could dismantle it and take away anything they wanted. The result was that the area was cleared in one day! Many of the nearby houses are supposed to have been built from this material. We climbed stairs to the roof of the gateway, from where there is a splendid view of the Taj set in its formal garden. Walking along the paths by the side of the water-filled channels and fountains we reached the high marble platform which forms the base of the Taj itself, and here, we had to either take off our shoes, or put on large canvas overshoes. This was both to protect the marble flooring from wear and also to respect the fact that it was a Muslim holy site where shoes must not be worn.

We entered the main domed building in the centre of which are two marble cenotaphs to Mumtaz Mahal and Shah Jahan. The tomb was originally designed by Shah Jahan for his favourite wife and so her cenotaph is placed centrally on the floor of the building. Times had changed when Shah Jahan died and his memorial was squeezed in to the left of that of his wife; of course, his is raised on a higher base! Both cenotaphs and their bases are of marble, richly inlaid with coloured stones in floral patterns. The floor is also of inlaid marble, the whole central area being enclosed by a screen of inlaid and fretted marble. Apart from the passageway around this screen which allows one to see the beautiful stone inlay, there is another passage around the building in the thickness of the walls. This connects small rooms under each of the four corners of the structure and is lit by windows to the outside. I was interested to see that the small panes of these windows were sheets of mica. It was also interesting to see the differing qualities of the coloured stone inlay work (pietra dura); this is said to be due to the differences in quality of the craftsmen, those from Italy being much more skilful than the locally trained workers. From time to time, a muezzin gave a loud call which resonated throughout the dome in a most impressive manner. Descending a flight of marble steps we entered the burial chamber on a lower floor which contains the marble tombs, arranged as before under the two cenotaphs on the main floor. This room has walls of polished marble and the two marble monuments are inlaid with black stone inscriptions in the Persian script. That of Mumtaz Mahal gives the 99 names of God, the date 1040 A.H. (A.D. 1630), and at number of religious quotations. Six, inches away to the west is the tomb of Shah Jahan. This is also inlaid in black stone with religious quotations and the date of his death 1076 A.H. (A.D. 1666).

At the time of our visit, access to the four minars at the corners of the Taj platform was regulated; a different one could be climbed each day, presumably to even out the wear on the marble stairs. On this visit, I was able to climb to the top of the minar at the north-east corner. The low marble balconies at several stages of the minars do not inspire confidence from the safety aspect, especially when wearing canvas overshoes, but the view from the top at 130 feet is worth the climb. At each side of the marble Taj platform is a sandstone and marble building inside the boundary wall. The one on the west is a mosque which has room according to a local guidebook “for 550 men to pray, including a number of women”! The building on the east side, is practically a mirror image of the mosque but is known as the Jamat Khana or rest-house. The Taj dome is surmounted by a large brass finial bearing a crescent and on the floor of the courtyard outside the rest-house is inlaid a stone outline of this to give an impressive indication of its size.

It is surprising that I remember these sights with great vividness but cannot recall what our party did for food and drink during the two days we spent in the Agra area. We certainly had breakfast and dinner at our hostel but must have had some refreshments during our rather long excursions over two busy days but I haven't the slightest recollection of this!

On this visit I bought a locally printed guide book which describes in a quaint manner the story behind the building of the monument. Here is an extract:-

The Emperor, in the year 1629 A.D. was going to the Deccan to fight with the Lodis, when he camped at Burhanpur, a favourite resort of Shah Jehan. The Begum was in camp, enjoying a game of chess. As the game proceeded, the Begum, who was in the family way, fancied that she heard the child cry in her womb. This being a bad omen for the mother the Begum became very anxious for her life and was horrified at the thought of death.

The Emperor ordered the most eminent physicians to diagnose her case and apply the best remedies. The Emperor was very sad and the physicians were trying their best when the Begum told her husband that she felt her health fail; and her heart was sinking. She told the Emperor that she had no hope of life left and feared the worst to happen any instant.

The Emperor, who was touched with those words, tried to console the dying queen, as best as he could, but she was not to be moved by the most touching little speech that the Emperor made to her. She, after thanking the Lord for the countless blessings that He had bestowed upon the husband and wife during their earthly career, asked two boons from the Emperor. The Emperor Shah Jehan who loved his wife dearly, promised solemnly to fulfil the two boons, which were, first, that he should not marry a second time as God had already blessed him with four boys and six girls. This was said with a view to avoid the arrival of first claimants to the throne, in case the second wife brought forth any children. Her second wish was that her tomb should be built of such a pattern and style that its equal may not be found in the world. He vowed before his wife to fulfil the two boons and the dying queen, having achieved her objects breathed her last. (In actual fact, Shah Jahan had two children by an earlier consort and eight sons and six daughters by Mumtaz Mahal between 1613 and 1631.)

Even from the time of Shah Jahan the Taj has needed some repair at times to cure leaks and replace missing stones, and during the 1940's work was started on tackling the many problems connected with the building. Decayed mortar was replaced and at one time the main dome was hidden by a mass of timber scaffolding. This was removed by 1945 when the American Army floodlit the structure to celebrate “VE Day”.

We next visited Agra Fort, about a mile and a half to the west, where the river Jumna makes a wide bend on its journey from the north. The fort is on the west bank of this bend. The walls, which are a mile and a half round, are seventy feet high with a lower outer wall and a wide, deep moat outside this. The fort was built largely by Akbar over a period of nine years from 1566.

We entered through the Amar Singh Gate at the south end of the fort. This gate is named after a Maharaja of Jodhpur who was executed by Shah Jahan. Nearby, outside the walls, is a monument in stone of a horse's head; our guide told us it was to commemorate a Rajput noble who escaped from the Mogul guards by jumping his horse over the walls. A short passage leads to the impressive inner gate through the 70 feet high walls and once inside these, we entered a complex of stone buildings known as the Jahangiri Mahal. This palace of Jahangir contains a number of rooms and courts that were built for his Hindu mother, Jodh Bai, purely Hindu in style with much elaborately carved stonework. The rooms were formerly decorated with great magnificence but now show only a few remaining traces of the painted and gilded floral decorations. As we moved from room to room our guide kept repeating that when the Jats plundered the fort in the 18th century they “looted and scraped” the gold from the walls, but when I questioned whether it had been worth the trouble, we didn't hear this phrase again.

Part of this palace, known as the Khas Mahal, was remodelled and extended by Shah Jahan using a great deal of marble instead of the red sandstone of the older work. Just outside this building is a large marble bath sunk into the paving. Built into its sides were alcoves or seats, presumably to allow a number of people to have a social bath in the fresh air; the waste water could flow from the bath through drain and our guide led us down a flight of steep steps near the fort wall to show how it supplied a smaller underground bath which was the sole water supply for the captives held in the prisons beneath the terrace. (I suppose that to drink second-hand bathwater was the ultimate insult!).

Lighting a candle, our guide led us along a number of dark underground passages until we reached a circular, domed chamber deep under the fortress. He called this the “Hanging Place” and a stout wooden beam with an iron hook was still to be seen. Apparently, there had been a deep pit in the centre of this chamber which led down to a passage connecting with the river, and the bodies of victims were disposed of in this manner. The pit had been closed by masonry for the sake of safety at some time in the past. The chamber had a foul, musty smell, and many bats hung on the walls and domed roof, and as our voices and candle light disturbed them, there was much squeaking and some of them flew round us while we were there. Altogether, it was a most unpleasant and evil place and we were all glad to get out into the daylight again. Near the Jahangiri Mahal I had a look into a great stone bowl standing in the garden. This is known as “Jahangir's Bath” as a Persian inscription round the top mentions him by name, but as it is five feet deep it doesn't give the impression of being a practical bath and its purpose is unknown.

Walking through the palace areas we came to the Throne terrace overlooking the river Jumna at the eastern side of the fort. Here is the Diwan-i-Khas, or Hall of Private Audience, built by Shah Jahan in 1636-7 as a place where he could receive ambassadors and dignitaries in private state. It is an attractive marble building with a covered verandah of three arches, raised above terrace level on a marble platform. In front of it is the Throne Terrace on which stand the black stone throne of Jahangir and the marble throne of Shah Jahan. Low railings of fretted, white marble edge the terrace which overlooks the open space below the wall, so that the emperor, sitting on his throne, could watch elephant fights taking place below the walls. We had a photograph taken sitting on the black throne with our guide. Some of the marble slabs at the edge of the terrace were almost blank, with lines of marking-out and only a few holes pierced through them for cutting the frets. At the time I thought that they had been left unfinished from Mogul times but it seems more likely that they were being made to replace damaged slabs and repairs were still going on. During the Jat attack on Agra, a cannon ball struck the black throne, scarring its surface, and ricochetted off to embed itself in one of the arches of the Diwan-i-Khas, where the damage can still be seen.

Away to the north side of the terrace was a building known as the Shish Mahal, or Palace of Mirrors, which contained a dressing room and a bath room, the bath being the usual marble tank set in the floor in the centre of the room. The room walls were covered with small irregular pieces of glass mirrors set into the plaster so that by lamp light it must have sparkled with light. The glass is greenish in colour and very uneven. An interesting feature of this room was the presence of slightly sunken panels in the walls behind which were hollow resonant cavities. (One was broken open so I was able to see the way it was constructed). While the queen was bathing, it was said that her slave girls would beat on these panels rhythmically so she could enjoy a musical bathe!

At the other side of the Throne Terrace and past the Diwan-i-Khas is the site of the Saman Burj or Jasmine Tower, at the north end of the palaces. This is a beautiful pavilion of inlaid marble built by Jahangir for his queen, Nur Jahan. It gets its name from the jasmine flowers inlaid in the marble in pietra dura. The pavilion faces the Taj Mahal across the wide bend of the river Jumna and our guide showed us how, by standing in a certain place, it was possible to see a perfect reflection of that building in the polished stone centre of a floral inlay. A very attractive effect. (Some years later, an Indian colleague of my brother Norman at Manchester University told him how the Mogul emperor at Delhi had a polished emerald through which he was able to see the Taj Mahal at Agra. At a distance of over 100 miles this seems most unlikely, and I wonder whether it was a garbled version of a story about the reflection at Agra Fort).

When Shah Jahan was deposed and imprisoned by his son Aurangzeb, he spent his last seven years here and died in this pavilion, looking across to his wife's tomb in the Taj Mahal. A short distance away, stairs lead down to underground rooms which we did not explore, only having time to go down one flight which took us to the Takhana or Royal Latrine, a small underground room fitted with a perforated marble slab seat which was set across a deep shaft, washed at the base by the waters of the river.

Our next visit was to the magnificent Diwan-i-Am or Hall of Public Audience which built in red sandstone by Akbar and later embellished by Shah Jahan with his usual marble work. As with the Diwan-i-Khas, it is built on a raised platform with rows of arches and carved pillars, but everything is on a bigger scale. The royal seat or diwan is set into the inner face of the building in an open-fronted room, raised well above the paved platform. In the side walls of this room there are pierced marble screens to enable the ladies of the court to see and hear all the proceedings in privacy. A small raised platform on the pavement of the building was provided for the vizier or prime-minister to stand on, so he could hand petitions and documents up to the emperor, and pass on his orders to the public. A daily public audience was held here when people could see the emperor, make petitions and get rulings on matters of justice and law, presumably after the payment of suitable fees and bribes.

By this time we were all getting rather weary so contented ourselves with only a fleeting glimpse of the beautiful Moti Masjid or Pearl Mosque which lay some distance to the north of here. It was built by Shah Jahan over a period of seven years. It has three domes and a series of pierced marble screens between the prayer places for men and women. We also had a quick look inside the Nagina Masjid, the Gem Mosque, which is a small private mosque of Shah Jahan and his ladies. This is a small, three-domed building, walled in on three sides to form a private and secluded courtyard.

On our way out of the fort we went into a showroom and shop where lots of souvenirs were on sale, inlaid marble, stone boxes, models and photographs. The stone inlay work in marble was done in a similar manner to that in the local monuments by local workers and some pieces were very fine. It was here that I bought an inlaid piece of marble, a black marble box inlaid with an outline of the Taj in mother-of-pearl, and a photograph of the building. It had been a very full day and we had seen lots of interesting sights but I was glad to get back to our hostel for a meal and a good rest. Before parting with our guide whom I had found very satisfactory and who spoke good English, I arranged for him to supply some transport for next morning so that we could have an expedition to the deserted city of Fatehpur Sikri which lies about 24 miles to the west of Agra.

Next morning, Sunday, the 23rd of February, we boarded a rather decrepit bus which our guide had arranged to take us to Fatehpur Sikri. It had no glass in the side windows but these were fitted with thin iron bars to stop anyone climbing out, and behind the driver's compartment was a small section with a bench seat for the “better class” passengers. The “common herd” travelled in the rear body of the bus. As there were no windows it was very dusty, especially towards the back of the bus so some of us travelled as “better class” passengers. The driver had an unusual method of fuel economy; he put his foot down hard and drove the bus up to its maximum speed of perhaps 40 m.p.h. and switched off the engine and put the gear into neutral. Then he coasted along until the bus had almost stopped when he re-started the engine and repeated this procedure for the rest of the journey. He wouldn't change this method despite my arguments so we had an uneven and weary journey.

The road ran fairly straight and eventually took us through the Agra Gate through the extensive walls of the deserted city of Fatehpur Sikri. We stopped just inside the gateway and some of our party climbed up to the top of the gatehouse. Most of the interior of the city seemed to be wasteland as the buildings of the inhabitants of the place had been far from substantial and had crumbled away. However, the palace area with its solid stone buildings was extremely well preserved. There is also a small inhabited village to the south of the area of the palace and the great mosque.

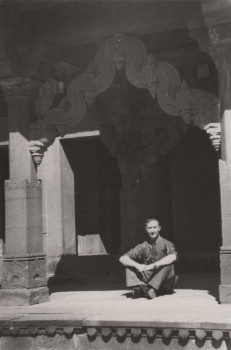

Leaving our bus on the road near the palace we set out to explore. We were able to wander freely wherever we wished as the area was almost deserted, only a few other visitors being seen. There was a wealth of fine red sandstone buildings which our guide explained to us, and although not as magnificent as those in Agra Fort, they were very interesting as they all dated from the same period of Akbar's reign, all work on the city ceasing in about 1586. We were shown buildings said to be stables for elephants and camels, and a vast series of palaces and courtyards set out in a spacious manner. Most were solidly built and functional but some were elaborately carved and it was possible to see Hindu influence in the apartments built for Akbar's Hindu wife, Jodh Bai. As I did not have a plan of the site, I found it difficult to keep track of where everywhere was! Some buildings were very memorable though, and these we looked at in some detail.

One particularly interesting building was the Diwan-i-Khas, or Hall of Private Audience, where Akbar would meet officials and dignitaries. It is a square building which looks as though it is of two stories from the outside, as it has two rows of windows. Internally, however, it is a square hall open up to the roof. A single pillar in the centre of the hall rises to about half the height of the building. The capital of this pillar is made up of many tiers of corbels, all elaborately carved, spreading outwards as they rise so as to form a large circular floor on the upper surface. From this floor four galleries cross the open space between it and the corners of the hall, where they are carried along the inner faces of the walls all round. The galleries and the central platform have low stone railings along their sides. By means of this arrangement, the emperor was able to meet his visitors without actually mingling with them, although he could receive documents and petitions passed across the bridges. Outside this building was a small open-sided, but roofed structure called the Astrologer's Seat. (Akbar was said to consult his astrologer daily having taken an interest in the beliefs of his Hindu subjects).

There is also a larger Diwan-i-Am, or Hall of Public Audience, as at Agra Fort, but much simpler in style. It takes the form of a large cloistered courtyard with an elevated verandah where judgements were delivered and petitions could be received. It has a number of pierced sandstone screens to allow the ladies of the court to observe the proceedings privately. In the nearby Pachisi courtyard is a low stone throne on which the players would sit to enjoy the game of Pachisi (a game reminiscent of Ludo) using 16 slave girls and servants, dressed in appropriately coloured clothing, as pieces on a board marked out in the paving.

Moving towards the Great Mosque, we next visited the Panch Mahal, which is a building of five floors, the uppermost being an airy pavilion which would catch the breeze in hot weather. It was built purely for pleasure. In the palace which lies near the stables towards the Great Mosque, the walls are pierced with elegant stone screens cut from the red sandstone. This was the palace of Jodh Bai, the Hindu wife of Akbar. Not far from here we entered the complex of the Jami Masjid or Great Mosque, through the Badshahi Darwaza, the south gateway, through which Akbar and his court came. The interior consists of a vast cloistered courtyard lined with numerous domed cells and containing two tombs, the most important being the tomb of Shaikh Salim Chisti, the famous Moslem saint, which occupies a prominent position on the north side. This tomb was originally built in red sandstone but was rebuilt in marble by Jahangir and Shah Jahan at a later time. As it was regarded as a very holy place we had to take off our shoes to enter the rather small building which has a rather elaborately carved marble exterior with pierced marble screens in the sides. Through the porch is a perambulatory around a central chamber enclosing the saint's cenotaph. This is covered with a rich inlay of ebony and mother-of-pearl which, I thought, could do with a bit of restoration as some of the inlay seemed very loose. Akbar attributed his success in producing a son (Jahangir) to the influence of this saint, and this is why he founded the city here. As a result, women who are desirous of a son come here to pray and when we visited the site, the marble screens around the tomb were festooned with pieces of cloth which had been tied on as offerings to the saint to obtain his good favour.

After looking round, we left the mosque through the great Buland Darwaza, built to commemorate Akbar's conquests in 1575. Rising above a high series of steps, it stands 175 feet above the ground at their foot. It is difficult to photograph as it is at the end of the ridge and the ground below it falls away steeply to the local village and it is not easy to get a complete view of this imposing gate which is said to be the highest in India. Outside the mosque walls is a diving tank of unattractive, murky water, into which enthusiasts will leap from the walls for a few coins reward. We watched two or three youths perform this feat and rewarded them when they came out dripping with dirty water.

We rejoined our bus and had a dusty, and weary journey back to Agra where we collected our kit and caught the Delhi train in the late afternoon. While waiting in the train at Agra station, I bought two carved wooden elephants from a boy, bargaining through the carriage window. He assured me that they were made of sandalwood - “Smell Sahib!” - and they did smell of sandalwood for a short time - until the spot of oil he had rubbed on them had evaporated! We returned to Palam with many pleasant memories of a most interesting few days but had to get down to work again on the Monday morning.

Although we were rather detached from affairs in the world except for the occasional newspaper in the Mess, the political life of India came to our notice at times. In London it had been decided that the British would quit India by June 1948. So, at least, we should get back home by then, and this was in our minds, even though it seemed an age away. The Army were releasing men according to their Release Group numbers, men who had been in the Services longest being released first. My Release Group number was 54c. There was no fixed timetable and men were released according to circumstances at the time so we never knew how much more time we still had to serve. An amusing incident took place at this time. I was on duty as an orderly officer and visited the B.O.R.s quarters one evening on my tour of inspection, to find most of the Signalmen huddled around a table and very absorbed in some matter. On investigation, I found that on the table they had arranged a large circle of pieces of paper with letters and numbers on them, and had an upturned tumbler in the centre. A number of the men each had a forefinger on the tumbler which was moving about over the table under their combined forces. One man with a paper and pencil was recording the letters and numbers to which the glass moved. They told me that they were consulting the “spirits” in order to find out when their release numbers would come up, and were very serious about it!

The Adjutant, Charles Tuck, was sent back to the U.K. by air for a short leave towards the end of February, his place being filled by Major Barnett, Indian Signals, and so I had to get used to sharing an office with a fresh officer. (Charles had left on LIAP leave; whilst the war continued, the Army had operated a scheme whereby any man who had served overseas for four years was repatriated. This was known as PYTHON leave, a reference to the Army eating its own tail. Towards the end of 1945, a new scheme was introduced named Leave In Addition to Python. Under LIAP, anyone who would have served overseas three years, before being demobilised, was to be given a short home leave). When Charles came back from leave, he told an amusing story about his journey home. Apparently the aircraft stopped at a French airfield overnight and with a few of the aircrew he visited a nearby small town. As they walked in the streets, he passed what he thought was a friendly remark in his best French to a young lady walking past, only to receive a wallop from her handbag which knocked him over. He couldn't think what he'd said wrong!

When he heard of our jaunt to Agra he decided he would like to go, so as soon as we could arrange it, we both went for another a weekend visit. We left Delhi on the evening train on Friday, the 14th of March, and arriving at Agra, sought accommodation in a pleasant small hotel, the Empress Hotel, a single-story building with a shady verandah, set in a quiet part of the city. On the Saturday morning we hired a tonga to take us to the Taj Mahal. As Charles wanted to travel back to Delhi fairly early on the Sunday, we decided to concentrate on seeing the Taj and Agra Fort and not bother with a trip to Fatehpur Sikri. We had a leisurely look round all the Taj buildings and gardens, climbing to the top of the south-east minar which was the one open to visitors that day. It was nice not to have a lot of others to look after and we both found the day very enjoyable. From the Taj we travelled in a tonga to Agra Fort and I showed Charles round all the buildings that the guide had shown me on my previous visit. Near the Khas Mahal I came across some Indian guides, among whom was the very man who had helped me on my last visit. I borrowed a candle stump from him and took Charles down to the underground prisons and the “Hanging Place” with its bats and foul smell. He was suitably impressed. I gave the guide back his candle with a small tip when we came out into the sweet fresh air again. The weather was getting hotter now and we were glad to get back to the shade of our hotel for a rest and a meal, but in the evening we went back to the Taj to see what it was like in the moonlight. It was most impressive in the gentle light, the dome seeming to float in space, and as we walked around between the rows of bushes along the paths, the sparks of fireflies flashed in the branches or flew through the air. There were some visitors walking round, but it was very quiet and peaceful, in fact, even during our earlier visit there were very few people about. We didn't enter the building itself but just walked round the entire site. After a leisurely morning on the Sunday, we caught an early train back to Delhi.

Towards the end of February, Lord Louis Mountbatten had been appointed Viceroy of India to replace Lord Wavell who held the position at that time. The turmoil between the Hindu Congress faction and the Muslim League about the future of the country led to violence and at the beginning of March, rioting in the Phnjab led to nearly 300 deaths. The problem was to decide how the country should be ruled, and whether it should be divided between the Hindu and Muslim groups. We were not involved at this time, the chief danger areas being in the large cities where there were mixed religions. There were always some political or religious demonstrations going on in Delhi and the Old City was out of bounds to troops, although we passed through it by road on our way to the station. One protest that was reported in the press was rather amusing. Hundreds of sadhus and Hindu mendicants congregated in New Delhi (“The All-India Association of Fakirs and Holy Men”), and blocked the streets around the Secretariat in a peaceful protest about the killing of cows (for food). The authorities dealt with this problem by bringing in the Army who loaded the peaceful protesters on to trucks and drove them off over 50 miles away and unloaded them. The streets were clear for a week or so before the sadhus made their leisurely way back, and the process was repeated until they got fed up with the protest.

Lt. Jones was posted away from Palam and I took over his section on the 18th of March. This was No.289 Terminal Equipment Section made up of Madrassi Signalmen with a Sikh Naik who was the truck driver. It was a very small and non-operational section and my duties were minimal. They had a store-room for their equipment which had to be checked in the taking-over procedure when we found that there was some duplication of equipment, so I took charge of a spare set of drawing instruments and some set squares to use in my office. These came home with me when I left India. The section was much reduced from what it had been and when I handed it over in turn to Lt. Chandler in May, it had been renumbered as No.4 Terminal Equipment Section, probably on account of the Army re-organisation consequent on changes to do with transfer of power. Apart from looking after the small number of men, I can't remember having much to do with this section.

On Saturday, the 22nd of March, the new Viceroy of India, Lord Louis Mountbatten arrived at Palam in his York aircraft and was met by Lord Wavell, the out-going Viceroy. Lord Louis wore his white naval uniform and was accompanied by his wife, Edwina, and their daughter. Nehru and other Indian government big-wigs were there to greet him, and we were able to watch the proceedings from a distance. After inspection of a guard-of-honour, they all set off in a stream of big cars for New Delhi and left us in peace. Next day, the ceremony was repeated in reverse as Wavell was seen off in the York aircraft that Lord Louis arrived in. On this occasion, Lord Louis had changed from his naval uniform and was dressed in a suit. Photographs were taken by an R.A.F. photographer and I was also able to take a few pictures of the departure of the York aircraft myself from an upper floor of our block.

By the end of March, political disturbances intensified, with general Hindu versus Muslim violence over much of Northern India. In Bombay, 147 people were reported dead, with uncounted numbers in country areas. The Sikhs were also involved and parts of the city of Amritsa were burnt. By the 6th of April, over a thousand deaths had taken place and troops were called in to restore order. I was involved in an interesting duty at about this time; I was made a member of a Court of Inquiry ordered by the Army to investigate the loss of a considerable quantity of firewood (lakri) from railway wagons in some sidings near Delhi. Firewood was an important commodity, being used for cooking and heating by everyone, and these were military supplies. The firewood was usually in the form of trunks, branches and roots of trees and was brought in by rail from some distant source. When the cargo was weighed it had been found to be seriously underweight, so the loss had to be investigated.

The Court of Inquiry was held in the Red Fort, Delhi, and lasted for about a week or so. During the intervals between sittings and at lunch times, I had good opportunities to take a look round the Mogul buildings in this impressive fort. I travelled daily to the Red Fort, being picked up by an Army engineering officer who was based in Delhi Cantonment, the large military area to the north of Palam. On our way to the Red Fort we picked up an Indian officer who was another member of the court. For transport, the engineering officer had a most unusual vehicle, a brand-new mobile laboratory, the interior of which was equipped with a complete set of apparatus and chemicals for the testing of lubricants and fuels, all in new and unused condition. There was a chemical balance and analytical weights, drawers of chemicals, standard equipment for the measurement of viscosity and flash-point and much more.

The inquiry was tedious as we had to interview lots of people concerned with the problem, only some of them speaking understandable English. It was a slow process as there had to be a translation of every sentence into English. I undertook the recording and wrote down the proceedings as they took place. I was involved in some of the questioning but as it had to be translated or explained to the witnesses, this was tedious. The engineering officer was the President of the Court and his knowledge of Urdu was less reliable than mine so we had to rely on the Indian officer and a translator. It was obvious from the start that it was a plain case of theft as the weight of wood missing was considerable, but it was not possible to lay the blame on any one individual, and in fact, the evidence seemed to point to the local population as the culprits. However, the Court had to work its way through all the evidence and take statements from numbers of railway staff, clerks and chowkidars, and finally reached the amazing conclusion that the missing weight in the consignment was due to the evaporative loss of water as the wood dried out! Considering that there had been no rain since the monsoon of the previous year, this seemed a very remarkable conclusion to me, but the Court was anxious to reach a verdict which did not lay the blame on anyone, so this was the decision. Typical Indian bureaucracy! My manuscript report of the Court was taken away and I never heard any more about the matter.

For me, it was much more interesting to have a look around the inside of the Red Fort, and although I did not have a plan and access was restricted, I was able to see some of the more important buildings. The gateways into the fort were impressive. Designed for the passage of elephants, they were quite high, as an average elephant stands about 10 feet at the shoulder and with a covered howdah its total height would be about 16 feet. Elephants can crouch down to get a back load under a doorway, but only to the extent of about one foot. The main gates were protected by outflanking barbicans so that they could only be approached from the side. These were built by the emperor Aurangzeb, much to the annoyance of his father, Shah Jahan who complained that they spoilt his outlook from the palace.

Inside the fort was a complex of buildings old and new, with the usual Diwan-i-Am and Diwan-i-Khas of Mogul palaces. The latter was a beautiful marble building with carved and stone-inlaid marble pillars, and was the original site of the fabulous Peacock Throne which has been estimated to be worth twelve million pounds at present values. After the decline of the Mogul empire, this bejewelled masterpiece was looted by Nadir Shah, the king of Persia, in 1739. The Moguls originally came from hot, arid regions of central Asia, where their public assemblies were held in large airy tents, so, when they built in stone their buildings were open-sided, and shady. They also delighted in flowing water in fountains, cascades and channels, and I was interested to see wide marble channels which had been used for water in some of the palace buildings in the fort. According to Jahangir's journal, 32 pairs of bullocks were permanently at work raising water from wells to keep the fountains playing in one garden near Agra.

I was able to have a look in the Moti Masjid, an exquisite small mosque in simple style, built by Aurangzeb, but did not get a chance to explore the baths and other buildings nearby. Looking over the east wall of the fort, I saw, over a wide dry moat, the detached fortress of Salimgarh. This was once used as a prison but seemed deserted when I was there. The Red Fort was built by Shah Jahan in 1648 as a palace citadel in his city of Shahjahanabad (Old Delhi). The city walls had a circuit of four and a half miles but much has now been destroyed: we drove through the surviving Delhi Gate in the walls on our way to the railway station, passing along Elgin Road in front of the Red Fort. Elgin road runs across the Maidan, a wide open area of grass and trees which was cleared of city houses after the Mutiny in 1857.

On the west side of the Maidan, opposite the south-west corner of the Red Fort, is the Jama Masjid, said to be the biggest mosque in India. It stands on the highest part of the city and has three large marble domes, inset with strips of black stone. Another of Shah Jahan's masterpieces, it is a striking building. Unfortunately, owing to the unsettled state of the city, and the lack of opportunity, I wasn't able to visit the Jama Masjid and only saw it from a distance. For the same reason I wasn't able to visit the city, itself, through which an important street, Chandni Chowk, runs east-west.

Chandni Chowk is famed for its bazaars where you can buy almost anything under the sun. The street was laid out in such a direction that the emperor could see along it while he was sitting on his throne in the Diwan, and this was the view that was spoiled when a barbican was built before the Lahore Gate of the fort.

We kept hearing of severe weather in the U.K. Heavy snowfalls blocking trains and a consequent fuel crisis. Also much hard frosty weather. This was difficult to appreciate as we were beginning to experience the onset of the hot weather, and changing our routine to suit. Our bearers would tidy our rooms and close the doors and windows after we had gone out in the morning. We started very early in the morning and returned about midday for a meal; after this we would resort to our rooms which were still full of cool morning air, and retire to our charpoys for a few hours sleep until wakened by our bearers with afternoon tea in the late afternoon. By this time the rooms were warming up and it wasn't until darkness fell that it was as cool outside as inside, and we could leave the windows open for the rest of the night. I usually slept on top of a sheet, with only a towel over my stomach to prevent it being chilled by the ceiling fan overhead.

We took salt tablets with our meals and I drank several quarts of water a day from my thermos flask which my bearer kept replenished as quickly as I emptied it. A water bowser was filled by the R.A.F. and salt added, after which it was driven round the airfield for a time to mix it up. It then stood in a shady spot so that anyone could get drinking water as needed. If a certain amount of salt was not taken, the results were severe cramps, which I am glad to say I avoided. It was usual to see saucers of salt tablets on the tables at meals as well as Mepacrine tablets for those people who were on regular dosage on account of flying operations in Burma and other malarial places.

When it got really hot, I would have four or five showers a day, finding this very refreshing; the water was never cold from the mains and it never needed warming up for a shower. Late on one very hot afternoon when I came out of a shower cubicle, there was a revolting-looking dog lying on the floor nearby in the shower room with its eyes closed. It must have come in after me as the room had no doors. We were always concerned about rabies in stray dogs, or even in pet ones, as there was no cure for hydrophobia if you were bitten. Wearing only a towel, I felt rather vulnerable so retreated into the cubicle and closed the door. I had picked up a dustbin lid which I dropped over the door about a yard away from the dog, making a tremendous clatter. The poor creature was so far gone that it took not the slightest notice, so I escaped to my room and got the R.A.F. to deal with it. I felt very sorry for the poor creature but was not prepared to risk a bite and the possible nasty consequences. Stray dogs were usually shot as they were a great danger to aircraft on the runways.

When we went into New Delhi at this time, some of the buildings including the banks were covered outside with sheets of matting known as khas-khas tatti which were drenched with water by coolies from time to time in an effort to keep the interior at a bearable temperature. In the colonnaded and shady arcades of the shops in Connaught Circus, street sellers congregated and I remember one small boy trying to sell one-stringed fiddles simply made from a stick and a small unglazed earthenware bowl with a membrane across the top, the thin string being wound to critical tightness to produce an appalling high-pitched screech. He was playing this unpleasant instrument to us and trying for a sale when the string snapped with a loud crack. We had to laugh at this and he also burst out in a rueful laugh as he saw the funny side of it. I never saw anyone buy one of these noxious toys!

It was very hot after the mornings in New Delhi and we did not go there quite as often as formerly. When the capital was moved here from Calcutta in 1911, the original idea was that the entire government should move to the cooler heights of Simla at 7000 feet each April and return in October after the hot weather was over. However, this proved to be impracticable and everyone had to sweat it out at New Delhi.

One day, the R.A.F. were burning masses of old documents on a bonfire not far from my office, and among the material being destroyed were large numbers of sheets of the 1:1M map of India which they used for aircraft navigation. I was able to salvage a number of these, covering all of south and central India and some northern areas. As I wanted to take these home with me I typed a short note to certify that they were obsolete and redundant, and got Lt.Col. Mullholland to sign it for me. On returning home, I cut them up and bound them into a book which I still have. I was engaged in much clearance of old files and documents myself at this time, and while doing this I acquired some letters written by Indian Signalmen and others in the form of applications for various favours and the solution of personal problems.

I had already received some of these myself when I was a Section Commander at Poona. I had one by post from the mother of one of my drivers (A6940. Sigmn.Rajmal); it was written in Urdu which I was unable to read and I had to get a translation from my Havildar, Prem Chand. It had been written by a professional letter-writer, endorsed as genuine by the local village “zaildar”, and “signed“ with the thumb-print of the originator who was obviously illiterate. Apparently, the family had arranged a marriage for Rajmal, and having made an outlay of 1000 rupees on the ceremony they wanted to make sure that he could get leave from the Army to take part. This petition had to be submitted to the Company Commander at Bombay through the “usual channels” and I cannot now recall whether Rajmal got his leave or not. Anyway, I acquired the original document from files that I was clearing out when I left Poona. Some of these petitions were quite pathetic and were considered sympathetically but others were of a frivolous nature and no further action was taken.

During the hot dry weather we were not too much troubled by insects, but there was no shortage of large black ants which raced about on the concrete verandahs with their abdomens held up in the air. I don't remember any coming into my room but as I never kept any foodstuffs in it, there was nothing to attract them. On the rough, coarse-grass covered ground around, these ants had runs radiating from their underground nests and in some places there were well-defined tracks worn bare of vegetation by the passage of streams of foraging ants. One such nest was under the concrete of a covered verandah leading to the Mess and was dealt with by the staff by pouring in a mixture of DDT and paraffin oil. The ants worked valiantly to clean their nest, large numbers of workers carrying crumbs of contaminated soil in their jaws and dropping it about a foot or so away to form a circular ridge. Many of them succumbed to the DDT in the process and their bodies were carried out and dumped with the contaminated soil. By the next day, the nest had been wiped out, but there was no shortage of others away from the buildings.

Early in May, I was approached by some of the B.O.R.s who asked if I, in my capacity as Education Officer, could arrange for driving lessons for a small number of them who were keen to learn. I thought this was a good idea and mentioned it to the C.O. He approved, so I got the job of organising classes. They had to be held on Sunday mornings as we worked during the rest of the week and the weather was getting very hot in the afternoons. I was the instructor, and to begin with had three or four interested learners to teach. None of them had any previous knowledge of driving so I had to start with first principles. To be on the safe side, I started with an introduction on the concrete runways of a deserted airfield at Gurgaon, about eight miles away from Palam to the south-west.

We used a 3-ton truck from my Section and had to be accompanied by the Sikh driver who was responsible for his vehicle. The learners took it in turns to drive on the runway where I taught them starting-off, stopping, how to change gear, (double-declutching!), steering and reversing. Those not involved rode in the back of the truck with the driver and probably found it extremely boring! After a number of training sessions at Gurgaon with plenty of room to manoeuvre and turn round, (free of obstacles), we progressed to driving in parts of New Delhi which were not likely to be badly congested. This fitted in with my interests as I was able to visit historical sites that I had not been to before.

The roads of New Delhi are laid out in geometrical fashion, long straight avenues radiating from circular junctions, which made it ideal for driver training. There were no traffic lights, pedestrian crossings or difficult junctions and the streets were very quiet with hardly any traffic in the area we used. One Sunday morning we drove to the far south-east of the city to visit the tomb of Humayun near the river Jumna. The men took it in turns to drive and we got there and back without problems.

I wanted to see this important monument and as we had the whole area to ourselves it was a most interesting visit. Humayun, who died in 1556 was the father of Akbar, and consequently is buried in a very beautiful and imposing tomb. It stands in a large square enclosure containing lawns and trees and stands on a large, arcaded, stone platform in the centre. The impressive tomb building is of sandstone and marble and has a large marble dome. On the roof around the great dome are domed pavilions which were originally used as a madrasa, or Islamic college. After the exterior with its marble inlay work and carved texts, the interior was disappointingly bare. The whole plan is perfectly symmetrical in layout with stone-lined water channels running away from the centres of the base platform. The whole area round the tomb is a complex of Mogul monuments as it appears to have been a favoured spot for burials, being near to the shrine of the Moslem saint, Nizam-ud-din, who was involved with the quarrel with Ghiyas-ud-din Tughlak in 1321. The latter took exception to being cursed by the sheikh and vowed vengeance on his return from a campaign in Bengal, but Nizam-ud-din's reply was “Dilhi dur ast!”, meaning, “It's a long way to Delhi”, and sure enough, when Ghiyas was one day's march from Delhi on his return journey, he was killed in an “accident” planned by his son.

On the way back to Palam we drove past the tomb of Safdar Jung, the Wazir of the emperor, Ahmad Shah, who lived in the mid 18th century. This monument lies near the Willington airfield and must be quite a landmark for the pilots of the New Delhi Flying Club who use it. Safdar Jung's tomb is a rather inelegant building built of unattractive looking, poor quality stone, and has a bulbous dome typical of the very latest Mogul style. Even so, it was quite a landmark which we often saw from a distance in our travels round New Delhi. Unfortunately, we did not have time to stop to visit Safdar Jung's tomb and had to be content with a distant view.

On another Sunday morning, I took my class for a drive through the Civil Lines which lie to the north of Old Delhi. We crossed the Grand Trunk Road which was formerly the military highway to the north-west of India, and drove along the Ridge. This was the base for the British Army through the hot weather of the dreadful summer of 1857, as they planned the assault on the mutineers in the Old City. There were many sites of historical interest hereabouts, but we lacked the time and local information to look for them in detail. On our return journey we drove past the very attractive Birla Hindu Temple which lay on the west side of the road leading south towards the Viceregal Estate on the west side of New Delhi. I would have liked to have gone inside but, owing to the unsettled conditions at that time, decided we had better not venture any more serendipitous sightseeing.