Chapter 4: School Days

In 1925 I started at Farnworth Church of England School, a walk of about half a mile from our home. Mother took me there to start with but I soon went on my own, coming home for dinner each day. I started in the Infants' School, an old building, built about 1844, with separate classrooms for boys and girls, the boys only up to age seven, but the girls up to age fourteen, the normal leaving age at that time. There were two teachers that I recall, one was Miss Guest and the other was Miss Edith Tickle, the former saw me through the intricacies of learning to read and write. Miss Guest would write elegant letters on a lined black-board for us to copy, but the only other subject I can recall was Plasticine modelling, and this only because I assumed that the Plasticine issued to us individually was a gift to be taken home. I was gently reminded that this wasn't the case! Looking upwards to the right from my desk through the high narrow windows of this classroom I could see the chimney pots of the adjoining caretaker's house, and I think this was the first time I ever saw the shimmering effect of hot air rising from a chimney. I can visualise it now. What an odd thing to remember from the age of five!

On reaching the age of seven, our class was transferred to the “Big-Boy's” School, a building of 1895, where we carried on our education until the age of fourteen, when it was customary for most boys to leave school and begin work. A Scholarship exam could be taken when we were eleven which offered the more able pupils a chance to go to the Grammar School, or the less able to progress to the Supplementary School in Kingsway, where the teaching was less academic. A school photograph taken of us in 1927, as we were transferred to the “Big-Boy's” School shows forty-two boys, dressed for the most part in woollen jerseys, some with knitted ties, and wearing short trousers, knee-length woollen stockings and lace-up boots. Five wore jackets or a blazer. I was rather heavy on boots which Father had to repair with pieces of leather, and he threatened to get me some clogs, which really worried me at the time as only a few of the boys from very poor families wore clogs and I felt myself a cut above these and would have been very humiliated if I had been made to join their ranks.

The “Big-Boy's” School stood to the west of the Infants'/Girl's School, each building standing in its own playground which was separated from the other by a high brick wall. There were two classrooms, a small one for the first class and a long hall-like room, stretching the whole length of the building, which could be divided into three by long dark-green curtains to provide for three separate classes. There was a corridor along the side of the larger classroom, and a cloak-room opened off this to the left. The school lavatories were outside, across the yard in a small squalid building. The facilities were very basic, and even as a boy I found the place revolting. The upper part of the playground on one side of the school building was flagged, the remaining, greater part to the west and the south being covered with cinders, unfriendly to bare knees. A picture showing the Pit Lane frontage of Farnworth School with its railings and gate, taken in 1905 shows no obvious change from what I remember of it in the 1920s. A typical group of young ruffians appears in the picture, on Marble Derby Day, a custom that was extinct by the time I was there.

We spent our first year in the smaller classroom under the firm control of Miss Tickle, a much more formidable person than her sister who taught in the Infants' School. Miss Tickle held us in awe with her habit of sharpening pencils with a large, razor-sharp carpenter's chisel, and her call for “Anyone need a lead sharpened?” always attracted customers. First thing every morning she would check that everyone had a handkerchief, and dole out sheets of toilet paper to those who couldn't produce one. We sat at long wooden desks with inkwells and at the front of the class stood a blackboard and easel. On the front wall of the classroom was a large World map on Mercator's projection, and how good it was to see such big red patches showing how extensive our Empire was at that time! We were all patriots and on Empire Day (24th May) anyone who was in the Scouts or Cubs could attend in uniform.

I don't remember much about our lessons except that we must have had some about singing, as I recall being mystified by the Tonic Sol-Fah to which we were introduced but we all enjoyed the actual singing which we did with gusto. Another detail that I remember was a large highly-coloured picture depicting the “Ancient Britons”, skin-clad and sitting outside their cave (or a hut). I think the picture also included a chariot fitted with scythes.

Some of our pastimes stick in my mind. There was a craze for making “racing cars” out of pencil erasers using drawing pins for wheels, and it was in this class that I learned how to make a “tank” from a cotton bobbin, a slice of candle, a matchstick and an elastic band. This first class had little contact with the rest of the school and except for playtimes we were in a self-contained little world of our own. Of course, at playtimes we did get a fair amount of bullying and there were often fights between the more aggressive boys and we would all gather round and watch.

At Farnworth School we had a number of traditional beliefs which were passed on without any justification. Some of them were old traditions that had been handed down for many years and some had arisen in modern times from some unknown source. I can remember some examples:-

- Swans are very dangerous birds and can break an arm or a leg with one blow of their wing.

- No one can swim across a pond because the green weed “Jenny Greenteeth” would drag them down.

- If an earwig got into your ear it would gnaw through into your brain.

- A pig cannot swim as in water it would cut its throat with its trotters.

- A cut between thumb and forefinger leads to “Lockjaw”. This was considered more certain if the cut was produced by a rusty nail.

- If you are chewing liquorice root and accidentally swallow the fibres they will accumulate round your heart and strangle it.

- An eccentric millionaire would give lots of money for the “right” pattern of an “aeroplane” on the fold of a cigarette packet. (These “aeroplanes” were actually colour printing registration marks).

- Dandelion seeds were known as “Sugar stealers” and were popularly supposed to enter house windows for this purpose.

- Any coloured butterfly as opposed to a common white one was known as a “Frenchie” and was eagerly chased.

- “Pignuts” could be eaten - but no one ever knew what they looked like and many a plant was dug up to look fruitlessly for them.

After a year in the first class, we were split up and shared between the three classes in the large classroom. There were three teachers; Mr Smith the Headmaster, Mr “Mickey” Brown and Mr Mills who walked with a limp. I went into Mr Mills' class at the west end of the large classroom; this class contained all those who later took the “Scholarship Exam”, the equivalent of the later “Eleven Plus”, so we were, presumably, included in the “brighter” group, although I didn't realise it at the time. We had an Assembly each morning, when the two big curtains were pulled back and we were all in one big room. Mr Smith played the harmonium and we sang a hymn, had a prayer and some days recited the Creed which was displayed on a large wall chart in front of us.

One of the most popular hymns was “Fight the Good Fight”, and I think that most of us enjoyed singing it, even though we probably weren't very tuneful. As it was a Church of England School, we were taken along Pit Lane in a group to St. Luke's Church for a service on special days. With luck, we could sit near the Bold Chapel in the north aisle and see the effigies on the tombs, often of more interest than the service. Of course, we had all been told about the “Bold” blacksmith who had fought and killed the Griffin from inside his iron cage in days long ago, but we were under no illusions about it being a rather tall story even if a good one. Of course, there was the actual Griffin Hotel at the bottom of Farnworth Street as confirmatory evidence! The church services were the formal Anglican ones of the time and a complete mystery to me, although we were well schooled in Biblical stories at school. When I told Mother how Mr Pike, the Vicar, intoned the service she said that I was making it up; perhaps my imitation was not very good!

Mr Mills walked with a limp and was rather stern and not averse to the use of the cane, usually on the palms of the hands. I don't recall being punished by him myself and it wasn't a frequent occurrence anyway, but he had no trouble in keeping us under control. There were suggestions among the boys that a hair across the palm of a hand would break the cane, or at least soften the blow but I don't think the experiment was ever tried!

I can't remember much about the actual curriculum but Mr Mills was a good teacher and would introduce variety into his lessons, often seemingly, on the spur of the moment - I can still remember some of these topics. Once he gave us a talk on pronunciation and vainly tried to get us to pronounce the word “towards” as “tords”. (We were not convinced). He gave us an interesting lesson on the human digestive system and the alimentary canal using a large coloured diagram and this aroused much interest. Such diagrams and maps, as well as the Creed, were displayed on coated canvas held between two wooden rollers. We had a lesson once on the meanings of idiomatic phrases which we had never heard of before such as “All my eye and Betty Martin”, and we had to write these down. He would come out with all sorts of snippets of information and I remember that he told us once that oak trees and men went “bald on top” as they became aged.

On several occasions he said he would bring a Davy miner's safety lamp and explain how it worked, and I remember being very disappointed when this lesson didn't actually materialise. Some afternoons, he would read us chapters from a book, and this was very enjoyable. I remember one story, a form of early science fiction, in which a scientist had managed to shrink himself and had all sorts of adventures with insects, for example, entering an ant's nest. It was an interesting way to describe the life cycle and behaviour of ants to children and we were fascinated. This fascinated me and I tried many times to get a copy of this book to read myself but without success.

The last part of Friday afternoons was given over to “Art and Handicraft” which took two forms. In one we were issued with tin boxes containing three small, round pans of paints (in primary colours) and set to paint a picture from a picture displayed on the blackboard. Mr Mills had a large folder of scenic posters that were pasted up at railway stations at that time as advertisements and one of these would be hung up for us to copy. The other activity involved the use of thin sheets of coloured card, which, using diagrams, pencil, rulers, scissors and paste we transformed into small boxes and such useless things as containers for spent matches. We were allowed to take these home.

There was a small glass-fronted bookcase in a corner of our classroom and this was the School Library, but as far as I remember, it was never opened for us to look into. However, on one memorable occasion it was opened by Mr Mills who took a book from it and gave it to me. The reason for this gift escapes me, but it must have been something special for I can't remember the bookcase being opened again. The book was about the various railway companies in Britain with lots of railway photographs and full-page coloured pictures showing the company liveries of engines. I have always regretted the loss of this fine book which I gave away to someone at a much later date, when my interests had changed.

Mr Mills must have had a special interest in railways as he gave all of us copies of paperback books on railways which had been published as advertising material by the Great Western Railway at that time. I had two different books which I read and treasured for many years. In 1930, there was a National Railway Week from the 13 - 20 September and he took us all to see the railway exhibition in St. George's Hall, celebrating the Centenary of the Liverpool-Manchester railway. A large railway track was set up on a long table and the various historic engines were run round it while a commentary was given. There were also many other exhibits in connection with railway history. I was interested in railways and one of my treasures was a booklet autographed by the driver of the “Flying Scot”. This famous train had been on a tour of North America at about this time and souvenir booklets had been printed.

I was friends with a number of boys in the class but there were others whom I avoided for one reason or another. My friends included Alfie Foster, who lived in Marsh Hall Pad to the east of Farnworth Street. (This trackway had been established by Bishop Smythe (ca. 1500) so that parishioners from Cuerdley could get to their Chapel in Farnworth Church without having to pass through the Farnworth Street in times of plague). There were also Ronnie Owen who lived at the east end of Alder Avenue with two aunts, Fred Patton from the farm at Cronton Hall, Don Machin who lived near me in Fairfield Road, and Harry Bates whose mother kept a public house in Millfield Road at the bottom of Peelhouse Lane. There was also a sturdy, bigger boy named Dickie Almond who I got on with very well. He had parts of some fingers missing on his right hand due to a farming accident with a mangel cutter. Although older than me, Dickie was backward in school work, and on one occasion we were sent out into the corridor together so that I could help him with his reading. We held a book between us and Dickie followed the words across the page with a large finger and read them out laboriously. After some time he became bored with this and we started to chat, soon being caught by Mr Mills who gave us a clip round the ears and took us back into the classroom.

I don't recall any teacher supervision during playtimes, and when fights broke out no one tried to interfere. We were left to our own devices until a teacher appeared to blow a whistle at the end of playtime. Anyone who was seen eating an apple in the playground was approached with the request “Bags me the core!” but the idea of eating a second-hand apple never appealed to me. The official sport of the school was baseball which was played on an adjacent small field. The boys who played this sport were chosen for their ability as there were some inter-school competitions. Rather unsurprisingly I didn't get chosen as I could neither hit or catch the ball with any success. I have no memory of any other sport being played, except for an impromptu football kick-about in the playground by some older boys, and I have no recollection of any physical training or drill of any kind. If there was any such activity, it must have made no lasting impression on me as I have retained no recollection of it whatsoever!

We played informal games in the schoolyard, the most common one being “Tick” (in some areas known as “Tig”). When this game was suggested, everyone would shout “Barley not On!”, (It has been suggested that this was originally “By your leave, not on”) and the last one to shout was “On” and had to chase and touch someone who then carried on the game. The whole playground was available but it was easier to dodge on the cindery part where there was much more room. On the south side of the school were two drainpipes from the roof, their bases being embedded in curved cement blocks; anyone being chased was quite “safe” if they could jump on one of these blocks and hold on to the drainpipe and we would cluster on these safe places at times.

A variation of “Tick” was “Relievo” in which a “prisoner”, confined to one spot, could be released by touching. If the defending boy could touch the boy attempting this however, he claimed another “prisoner”. Some of the younger boys played at “Bell horses”. For this two boys would link their crossed arms and trot round together in step, imitating the pairs of cart-horses which were used at that time to pull heavy wagons. These horses were usually decorated with brasses and often carried “rumbler-bells” on their head harnesses.

A rather rougher game was called “Ten Ton Weight”. For this game, one boy stood with his back to a wall with about three boys leaning towards him head to tail so as to form a long “back”. The participants in the game then ran and jumped, one at a time, trying to get as far as possible on the “back”. Sooner or later this gave way and became a tangled heap of bodies. It was a very rough game, especially as it was played on the cinders. It is interesting to see that a version of this game is shown in Brueghel's 16th Century “Kinderspiele”.

I had been to the cinema with Father, where we saw a dramatic film about pearl divers and the hazards they faced from giant clams and octopuses. It was entitled “White Shadows in the South Seas”. This 1928 silent film was in black and white, with rather heavy contrast, and interspersed with printed dialogue. This experience led me to devise a new game in which a group of us had to run the length of the cinder playground to the end wall (the bottom of the sea), holding our breath while a fierce octopus, usually Dickie Almond, tried to catch us with his long arms, before we could get back to the concrete flags. This energetic game became quite popular and we often played it.

Various games of “Marbles” were played; on the way home from school we sometimes would play “Bobalong”, rolling marbles along the path or in the gutter in attempts to hit one already thrown. There was also a “ring” game; each player placed a few marbles inside a circle drawn on the ground and then each player in turn attempted to “fire” marbles so as to knock them out. “Ironies”, as the superior steel marbles were called (usually 1” steel ball bearings), were rare and highly prized above the common glass “Alleys” and the smaller clay marbles that we generally used as counters. When marbles were not available, for example on a country walk, we would play “Duckstones” with rounded pebbles, trying to hit our opponent's stones in turn as we walked along.

Out of school I would sometimes play with Alfie Foster who lived with his parents and a younger sister in Marsh Hall Pad. They lived in an old house with a large, upstairs “workshop” and store-room in which we played. Over the living room fireplace was a glazed case containing two model stringed-instruments, possibly a mandoline and a fiddle, each inlaid with mother-of-pearl. I understood that these had been given to them by Mrs. Paravacini, of the family that ran the Asbestos-Cement Works on the east side of Derby Road, only a short distance away. Presumably, Mrs. Foster had been on friendly terms, if not employed, by this family at some time. A short distance from their house on the left side of Marsh Hall Pad, fields of rough pasture stretched as far as Lunt's Heath Road where there was a large, deep, water-filled pit known as the Clayhole, and one of our common amusements was to burn off patches of grass using matches. As there were many tufts of long grass we had some splendid fires, usually kept under control. Everyone knew what we had been up to when we arrived home smelling strongly of smoke!

Another of my school friends was Fred Patton whose father farmed at Cronton Hall Farm near Pex Hill, about two miles from Fairfield Road. They had working horses and pigs which I was interested in but I was more attracted by Fred's rabbits and a small flock of bantams he owned. The Hall was a very large building and was reputed to have a room for every week of the year, but it was only on one or two occasions that I was allowed inside and then only into the large farmhouse kitchen. We would play in the outbuildings and the barn and look at the animals. I suppose that this was my first experience of a farm. In particular, I was very taken by Fred's own flock of bantams. I was so fascinated by these that I pestered Father to get some in our back garden. After worrying him a lot about this, he finally said that, “some day” we might have a smallholding somewhere and then I could have some. That was as far as it ever went as apparently the house deeds forbade the keeping of poultry, possibly on account of nuisance to neighbours. He did relent to some extent and told me that I could have a pet rabbit, and we even went to the extent of building a hutch supported about a yard off the ground on four posts. It had a wire-netting front on the left and a door on the right. But, for some reason I never did get a rabbit. In later years however, when I became more interested in chemistry the unused hutch was useful to store some of the more smelly chemicals that Mother would not have in the house!

During my early years at the Boys School we all had a dental inspection by a visiting nurse and as a result, Mother took me down to the Dental Clinic which at that time was in a small building next to the Town Hall, at the corner of Market Street. Here I had the unpleasant experience of having a tooth extracted under gas anaesthesia. (I have no recollections of having a tooth-brush at that time but it would seem likely that my teeth had been cleaned at times, probably by Mother.)

I had only about half a mile to walk to school unlike my Father and his brothers who in their day had to walk to Farnworth School from Ditton, a distance of about two and a half miles. This involved bringing sandwich lunches and he used to tell how on one occasion, he was minding the sandwiches while his brothers were in an orchard after apples when they were caught by the owner and locked up in a shed for some hours to teach them a lesson. As a consequence, they had no lunch and Father had to deal with all the sandwiches himself! He frequently told us this story. I used to enjoy my walk to school as it lay through some grassy fields where there were several pits, our favourite being Robinson's, presumably named after the owner of the field it was in. It lay below a high bank on the east and was fed by a piped field-drain running along below the bank. It had a gently sloping and accessible shoreline on the north side and abounded in pond life, newts, frogs and sticklebacks, which we called “Jacksharps”. The male sticklebacks developed a red coloration in the breeding season and were known as “Redgobs”. They were prized catches.

The pit in the adjacent field to the east had no name and was rather over grown and much less attractive and we didn't bother with it much. Once, I remember seeing the bloated body of a dead cat in it which put me off visiting it, and was responsible for some bad dreams. We usually visited the pits on our way home when we were not tied to time, and often arrived home with wet and muddy boots and clothing. I got into trouble more than once after such a visit and I remember having to explain away one newt I brought home as one which was “almost crawling out of the water” and asking to be caught. This caused my Mother some amusement but I was warned not to go to the pit again. (A complete waste of her words, I'm afraid).

We crossed the railway line by a small foot-bridge, known as the “Tin Bridge”, and we always raced to get on it to see a train which blasted us with smoke and steam. Sometimes, we would scramble down the embankment and put pins or small nails on the lines in the belief that a passing train would flatten them out into useful small knives. To our disappointment, we never found any trace of our pins after a train had passed. One or two boys would climb on to the upper side of the bridge and walk across on the narrow girder, a highly-dangerous stunt. Another trick, at which we were all adept, was to run across the bridge kicking every steel panel with both our heels, which made a satisfying noise.

The walk home along Beaconsfield Road, at that time little better than a rough track, and across the fields to the “Tin Bridge”, was the most direct way, but there were alternatives. Sometimes we would go down Farnworth Street and back along Alder Avenue which gave us a chance to look in the shops; we could also go down Birchfield Road and over the bridge by Farnworth Station. On the west side of the road by the bridge, the stone retaining wall running from the bridge decreased in height until it was only a few feet above the field below. One game was to jump off this wall as far as we dared as it increased in height, in a competition; it is a wonder we didn't break our legs. I know mine were very painful at times after a session of such high jumps.

At the end of Pit Lane was Littler's Farm, and between Coroners Lane and the churchyard was the stackyard. When threshing was in progress we would go and watch this operation on our way home. A traction engine would be driving the threshing machinery with much smoke and steam and a great deal of noise. As the ricks were taken apart, rats would run out to be killed by dogs and men with sticks. I remember on one occasion that I picked up a large rat and took it home in triumph “for our dog to eat”. Mother was not best pleased so I didn't do it a second time. Another time I got into hot water was when they were felling some large sycamore trees around the church: having cut down the trees, they trimmed off the branches and left them on the road. I chose a large branch and dragged it home in preparation for Bonfire Night. Arriving home, I couldn't get it through the side gate so pushed it over the top with a great effort. When Father came home from work at night he found that he couldn't open the gate to get his bike in because someone had placed a big tree branch behind it. Of course, again, I got the blame for some reason.

As Christmas approached, we were always involved in making decorations for the schoolroom, and best of all I liked to make paper chains using strips of coloured paper, an easy task. I remember that one year we spent much time in making Christmas trees out of cardboard, cutting tree outlines with jagged edges and pasting green paper on them. Two of these shapes, slotted together, made either free-standing or hanging decorations. We used small bottles of unpleasantly smelling fish-glue for this work. The last day at school before the Christmas holidays was looked forward to and we all enjoyed it. We had been told to bring a brown paper carrier-bag, and after Assembly we sat at our desks while the teachers gave out a large number of card and paper puzzles and games, supplied by various firms as advertising matter. This happened every year I was at Farnworth School. At the end of the morning we each took home a bag full of these trifles which kept us occupied for days over the holidays. As examples of the things we were given, there were cards to cut up and make angular jig-saw puzzles, a card to cut out and make into a model of H.M.S.Victory - (advertising Victory V gums), paper disks with a carbon-paper backing, which, when rotated as directed and certain marks pencilled over, would reveal a picture and an advertising message, colouring cards, tangrams, and working models to make in thin card which only needed brass paper fasteners as axles. One that I remember was an amusing model of an old woman with walking legs. A popular trick was a plain sheet of white paper marked with a black spot at one corner. A thin strip had to folded down along each edge to support the paper on a plate. A glowing match or string applied to the marked spot would cause a line to smoulder across the paper to reveal the words of an advertisement, e.g. “Beecham's Pills”. I have never heard of any other school which had this Christmas treat.

In the afternoon, we returned to school carrying a mug and spoon for our Christmas party, where we had some refreshments and were each given a small present to take home. One year, I was given a penknife with one blade. On the way home, in the gloom of the December afternoon, we simply had to call at Robinson's pit. The weather had been rather wet and on the grassy bank above the pit was a large pool of water. We simply had to drain this into the pit by digging and kicking away the intervening ridge of turf and soil and my new penknife came in useful, but I got into some bother when I arrived home wet and muddy.

When morning Assembly was held at school and the curtains drawn back, I remember seeing a photograph on the wall showing Indians bathing in the Ganges at Benares, and also a small round shield of unusual shape near to where Mr Smith played the harmonium. At the time, I understood that it was a souvenir from the Sudan, but it was never explained to us in detail. I was interested in such relics especially as Grandma Hinde had shown me curios which she had brought back from her earlier life abroad. She had even given me some small items which I kept in a cupboard in the Lumber Room, marked as my “Museum”. Out of interest and a desire to show off my treasures, I took oddments to school sometimes. Once I took a cob of “Indian Corn” and was most put out when Mr Mills said it was largely grown in America and not India as I had supposed. There was also another curious object, beautifully made from several sections of hardwood, glued together with imperceptible joints, and with an aerofoil section. It was about 8 or 9 inches square. I was told by Grandma that it was a piece of a Turkish aeroplane brought back by Grandad as a souvenir from his Middle East service during the Great War. It was highly polished on the upper surface but the under-side was pitted slightly (perhaps by sand). Grandad had presumably intended to make it into a picture frame and had cut an oval hole through it. When I took this to school, I was rather put out when one boy said it looked like a lavatory seat. I must admit it did look like a small seat but the idea had never occurred to me. It always seemed too heavy to be part of the structure of an aeroplane and it may have been the tip of a rather large-bladed propeller.

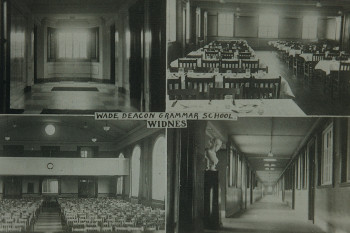

At this time the boys at Farnworth School only referred to their close friends by their Christian names, most boys being known by names formed by adding -ie to their surname. I was known as Adamsie for example, except to my close friends who called me “Jackie”. Towards the end of the 1920's, some of the boys were picked out to attend woodwork classes and went once a week to the old Grammar School in Peelhouse Lane, familiarly known as the “House of Flying Mallets”. I suppose that these boys were those considered to start work ultimately as tradesmen when they left school. In 1931 three of the boys in Mr Mills' class were chosen to be entered for the “Scholarship” exam, later to become the “Eleven Plus”. I was one of these and the other two were my friends Don Machin and Harry Bates. I don't recall any special tuition being given to us in preparation for this exam which was held in the “Supplementary” School in Kingsway, and I was impressed by the sight of an array of chemical glassware in a glass-fronted case in one corridor and thinking that I would like to have some lessons in chemistry. (I was already a dabbler with chemicals having been given a “chemistry set” for Christmas at some time.) We all passed the written exam but I must have been a borderline case as I was obliged to attend Widnes Technical College for an oral exam by Mr Green, the Headmaster of the Grammar School. He tried to stump me by asking “If a diamond is the hardest material known, what is used to cut it ?” I had never heard this fact stated before and had to do some rapid thinking before I said “Other diamonds”. As a result of these exams all three of us were passed and started at the newly built Wade Deacon Grammar School when it first opened in Autumn 1931.

Having passed the Scholarship Exam, I was given a place at the newly built Wade Deacon Grammar School which was officially opened on Thursday, the 10th of September 1931, having cost “in the neighbourhood of £60,000 to build” according to the special supplement published by the Widnes Weekly News to mark the occasion. I started in Form 1A, in a class of 29 boys, our form master being “Alf” Salt, a dour character who had been one of the first scholars at the previous Secondary School in 1897. We wore a school uniform with a blazer and cap bearing the coat of arms of the school. This was a shield divided into three sections, the upper two bearing a red rose for Lancashire and a beehive with four bees signifying industry. The lower section had a bishop's mitre, referring to the foundation of the Grammar School by Bishop Smythe in the 16th century. Under the shield was the motto - “Fervet Opus” - meaning “Work Ardently”.

Our form room was on the ground floor next to the assembly hall and we had individual desks containing lockers to store our books, P.T. kit and personal items. We could provide our own locks to secure them if we wanted. As we moved about the school from lesson to lesson, we had to carry all the books needed for these and only came back to our form room in breaks or before classes in them. Leather satchels were the rule but one or two boys carried small attaché cases. Lessons were divided into 45 minute periods and bells rang to indicate the time to move to the next classroom for the next period. This was the signal for a disorderly scramble to another part of the school, where sometimes, we had to wait to be let into the classroom until the teacher arrived.

There were three periods in the morning and four in the afternoon with breaks during the morning and morning and afternoon during which we went out on the playground and field behind the school. In due course we were sorted out into classes by the duty form master and marched inside. The school day started with a morning assembly in the hall for the boys, while the girls held theirs in the gymnasium. Together with school notices and prayers we sang a hymn from a hymnal and dispersed to our form rooms. I remember that the words of one of the hymns was in Latin and sung to the tune of Isaac Watts' “O God our help in ages past”. We also had a School Song “Forty Years On” which we sang from time to time, and which I now understand to have been cribbed from that of Harrow School.

Also in line with Public Schools we were divided into four Houses for sports:- Muspratt, Gossage, Deacon, and Dennis. Most boys wore cotton sports shirts with horizontal stripes of these colours but my Mother made me a knitted one in wool which soon went rather baggy, especially after a few rough games of rugby when others found it a handy thing to grip in tackles. Wednesday afternoons after the break were devoted to sports and we played rugby and football (not encouraged) in the winter months and cricket in the summer. We were also expected to turn up for sports on Saturday mornings but I felt this was too much of a good thing and didn't attend despite various threats by the school. I wasn't the only one either.

As I have mentioned, during the first year, “Alf” Salt (aka Mr A. Salt M.C.) was our form master and taught us English and Maths and also Scripture for one term only. French was taught by “Nag” Hall (aka Miss E. Hall B.A.) who was on friendly terms with “Alf” and would sometimes come into the classroom for a chat while we were given some problems to solve. History was taught by Miss McKinlay, a formidable lady for whom I cannot remember we had any nickname. She once asked us to produce some object related to our subject and I remember making a “cuneiform” tablet of clay which seemed to satisfy her. Geography was taught by “Aggie” Brown, a live-wire lady who came to school in a small rounded sporty car which we called the “Flying Egg”. She was a good teacher. For Physics we had “Billy Thom” Thomason, an entertaining and popular teacher who had the gift of bringing his subject alive in everyday language, free from jargon, and with simple physics experiments and demonstrations. I remember making a simple working electric motor from his instructions.

My progress gradually improved as shown by school reports which detail my form position rising from 20/29 in 1931 to 4/29 in 1935 when I took the School Certificate examinations, gaining Credits in English, History, Geography, Chemistry and Maths, and a Pass in English Essay but failing in French. Although missing some work due to absence with German Measles, I matriculated in July 1936 with Credit A in Geography and Chemistry, Credit B in Physics and Maths, Credit C in French and History, but only Satisfactory in English and English Essay.

During the Autumn of 1936 following matriculation, I entered the Lower VI Form at Wade Deacon Grammar School. We had fewer subjects to study but were starting on calculus, co-ordinate geometry and more advanced and mathematical physics and I found these difficult. It was even harder to settle as I was only waiting to get a job and had no intention of completing the course to Higher School Certificate. Nevertheless the Wade Deacon Headmaster, Mr Green was able to write of me in his school-leaving reference that “he is quiet and retiring and always cheerful and reliable. He works steadily and has more than average ability....I can recommend him very strongly and without any reservations whatever.” Armed with this supportive testimonial, I thus sought to enter the world of work.